Our Thinking

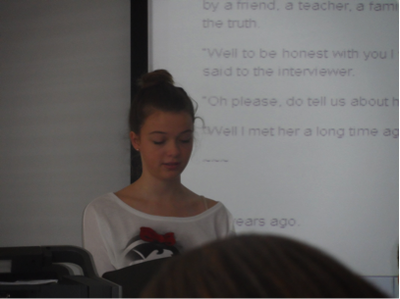

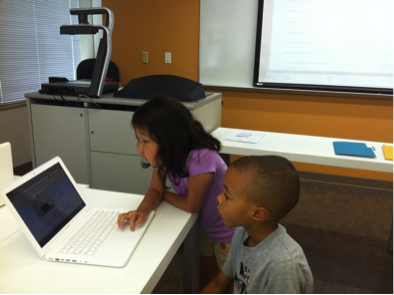

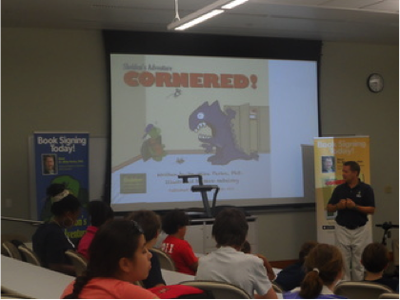

by Tresha Layne, Mark Meacham, and Amy Vetter Our previous blog described how we planned for the camp, including how those plans aligned with 21st century literacy goals (NCTE, 2013). This blog will discuss how those plans were put into action, including modifications we made based on the needs of participants. A typical day of the camp began with a whole group welcome in the UNCG School of Education auditorium and an author talk to inform and inspire young writers as they developed their camp publication piece. On the first day, campers met as a whole group in the auditorium to learn about some of their readers, students in Kenya. After her presentation, students asked questions, such as, “What do the kids eat the Melon Mission?” and “Is it hot there?” When students gathered in small group to brainstorm their writing, students also discussed how this audience shaped what they intended to write. For example, Jackson commented to two other campers that writing for children in Africa “changes the whole game” of writing for him. Such discussion about audience, then, began the process for students to think about how to design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes. All other camp days, began with an author. For example, on the second day of camp in 2014, a children’s book author described how he collaborated with a visual artist to create a multimodal children’s picture book. In sharing one of his tips on writing, he said, "find someone who completes you." After asking the young artists and then writers to identify themselves by raising their hands, the author said, emphatically, "get together . . . find someone who isn't exactly like you. That would be the best combination for creating a winning book." These interactions opened opportunities for students to foster connections and relationships with others that posed and solved problems collaboratively and strengthened independent thought. For example, after a poet shared his poetry, a high school student wrote poetry along with a non-fiction piece that he presented in a Prezi. In fact, some of the campers continue to stay in touch in with these authors and discuss their writing, so the collaboration and problem-solving persists even after camp is over. From there, writing teachers escorted students, divided by grade levels, to nearby classrooms equipped with computers and multimedia equipment. To develop proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools, teachers and writing coaches began with fifteen to twenty-minute whole group mini-lessons about 21st century literacy tools along with elements of the writing process before having students break into smaller writing groups for concentrated writing time and more individualized writing coaching and collaboration. For example, during a mini-lesson instructors demonstrated how a digital tool (Popplet) might be used to brainstorm and plan various kinds of texts. After learning about the tool many campers used it to help construct their texts. One camper, Sophie (rising eighth grader), used it to brainstorm and plan for a digital fashion magazine that utilized multiple modes of communication. In order to help campers develop proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools, teachers had to be intentional in their effort to comfortably use digital media tools themselves and had to be prepared to combat inevitable technical issues. From our observations, teachers’ comfort level in working with the digital tools played a big part in how well they were able to independently assist campers as they encountered issues with the digital tools. For the writing coaches in particular, many of the digital tools were new, so in some cases coaches were still learning digital tools along with their students. To resolve technical issues with digital tools in these cases, coaches relied on the support of camp colleagues or other campers. In some cases, resolving the technical issue required creative thinking. For example, one instructor had to figure out how to help a camper reformat his writing piece when it exceeded the allowable file size of the digital tool he wanted to use. To get around this limitation, the coach helped him remove his writing from the digital tool, place it into an alternate tool for special formatting, and then replace it in the original tool. To fully support campers’ ability to manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information and create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts, instructors and writing coaches anticipated the needs of the young writers. Most came with a planned mini-lesson based on the needs of the campers. For example, Maggie (a writing coach in the high school group) asked Jackson and Savannah to rewrite their opening sentence as a way to revise their final piece. To do this, both campers explored other first sentences of books, first lines of movies, and/or visuals (e.g., Jackson’s own drawings) as ways of hooking an audience. Both campers found this exercise challenging, but rewarding. In particular, when Jackson and Savannah shared their first sentences, they had the opportunity to critique and evaluate each other’s work in productive ways. Not all planned mini-lessons worked as writing coaches hoped they would. Although more stressful, they found that planning a lesson each night based on the needs of students worked better than entering the two weeks of camp with lessons already made. In addition, creating lessons that were interactive and situated students as experts fostered small group writing communities in ways that lecture-based instruction did not. Thus, teaching students about the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments (e.g., copyright), was more productive in small groups and when done while students were drafting and revising their pieces. Overall, making the camp a flexible, interactive, and informal writing community best supported students’ engagement in 21st century literacies. This included morning breaks with a brief snack and taking students outdoors for a quick writing break. In addition, concluding the camp with opportunities for young writers to share their writing at the university and a local bookstore enabled campers to share information with a broad audience. Audiences who attended these readings or read over the published pieces learned about the history of LEGOs, a thriller that involved shattered glass and a wounded father, and a drama about a kid who saved the world. Dividing these readings into manageable sessions (approximately 10 students for one hour) enabled students to share all or a portion of their work while not overloading the audience. Thus, campers needed time to practice reading aloud with a clear speaking voice and keeping within their allotted time limit. To read more about what we learned from the camp experience, check out our next blog. NCTE Executive Committee (2013). NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/governance/21stcenturyframework.

0 Comments

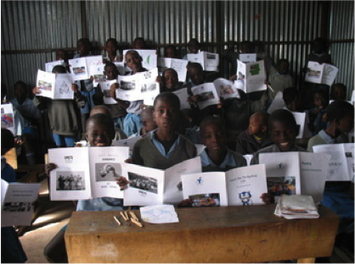

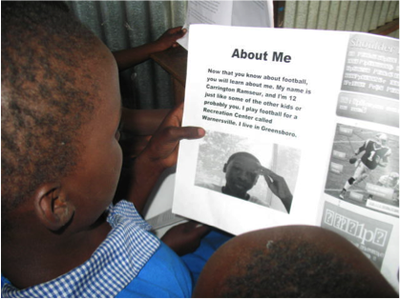

by Amy Vetter, Mark Meacham, and Tresha Layne For the past three years, the University of North Carolina Greensboro has hosted a two-week Young Writers’ Camp for students in grades 3-12. After the first year, the committee decided to dedicate the two-week camp to 21st Century Literacies. In other words, we wanted to create a space for young writers to collaborate with other writers, read and produce multimedia texts, and share information with other young writers across the globe. The purpose of this blog is to write about how teacher educators, doctoral students, and public school educators’ worked together to set up a camp dedicated to writing in the 21st century. Two blogs will follow that describe how the camp actually worked and what we learned from the process. The first year of our camp was split into two sections: one dedicated to creative writing and one dedicated to informational texts. As former and current K-12 teachers, we viewed the focus on these two areas of writing to be limiting for students. In addition, the divide between the two did not illustrate the realities of writers today. Starting the second year, campers attended both weeks, chose to write in their preferred genre, and used digital media to construct and publish their final piece. To prepare for this new vision, we developed a shared understanding of what we meant by 21st century literacies. Specifically, we drew from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) (2013) who state that participants of 21st century literacies, do the following: ● Develop proficiency and fluency with tools of technology ● Build intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others so to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought ● Design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes ● Manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information ● Create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts ● Attend to the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments To create a camp that fostered the above characteristics, we first collaborated with colleagues at our university and surrounding public schools. To begin, we hired four instructors (certified literacy teachers) and placed them in rooms with 15 campers divided by grade level (3-5; 6-8; and 9-12) who met for two weeks from 9 am to 12 pm. We had two elementary groups. Along with the instructors, we worked with faculty members who taught a graduate-level Teaching of Writing Course that occurred during the two weeks of the camp. Instructors agreed to use the camp as a field placement for graduate students (all K-12 certified literacy teachers) to try out strategies they learned in their course. The faculty members who taught this course prepared the “writing coaches” to engage in a writing workshop approach, including planning mini-lessons based on the specific needs of campers. Students also read various texts to help prepare them for this endeavor, such as Crafting Digital Writing: Composing Texts Across Media and Genre by Troy Hicks. In addition, writing coaches and instructors came prepared to help campers manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information and create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts by sharing mentor texts and guiding students through research strategies for both creative and informational texts. Along with these instructional approaches, writing coaches and instructors planned to educate campers about ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments, including copyright issues and plagiarizing. To help with this, we hired two technology coordinators who created email usernames and passwords that we gave to parents to ensure online safety, especially with the younger campers. We also bought flash drives for campers to save their material so that if they did not have to access to the web after camp, they could work on their piece at home. Finally, our instructional approach included the development of proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools that campers used, such as Voicethread, Weebly, and Comic Life. To help prepare those teachers for these new tools, the camp committee developed a list of resources campers could use, along with some information about how to use them with young writers (definition, examples, links to tutorials, and suggestions for exploration). Writing coaches and instructors in the elementary group decided to focus on a select amount of mediums, while middle and high school were open to choosing whatever digital media tool students preferred. To foster intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others that posed and solved problems collaboratively and strengthened independent thought, we contacted local and national authors about speaking with our young writers about their work and their writing process. We invited novelists, poets, children’s book authors, bloggers, journalists, graphic artists, documentary producers, etc. Some authors lived in the area, while others Skyped in from other cities and states, such as New York. These authors were asked to share their writing, discuss their writing process, and answer questions from the audience. All of the authors were expected to interact with students and engage them in some kind of composing activity. Feel free to browse our author list. We also worked with developers of The Melon Project, a non-profit organization that works to better the lives of children and their families living in Nakuru, Kenya. One of the objectives of the organization is to offer basic education to the orphans and destitute so as to join the mainstream of other school going children. For the first day of each camp, we asked an organizer of The Melon Project to describe the purpose and people behind the organization. We planned to have published pieces from our young writers to be sent to Kenya and used as a learning tool for these children, especially to aid in the learning of English and American culture. This enabled campers to design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes. Campers also read aloud their published pieces on the last day of camp with an audience of community members (i.e. family members and local educators) and/or at Scuppernong, our local bookstore. Check out our camp publications here. Although we planned for the camp to work as described, we made modifications based on the needs of our campers, instructors, writing coaches, and access to digital media. In our second blog, we discuss how the camp actually worked, including more details about the ways in which campers engaged in the specified characteristics of 21st century literacies. NCTE Executive Committee (2013). NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/governance/21stcenturyframework. Hicks, T. (2013). Crafting Digital Writing: Composing Texts Across Media and Genre. New York, NY: Heinemann. |

Contributors

Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed