Our Thinking

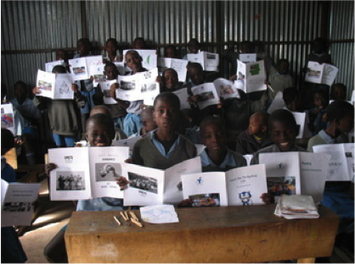

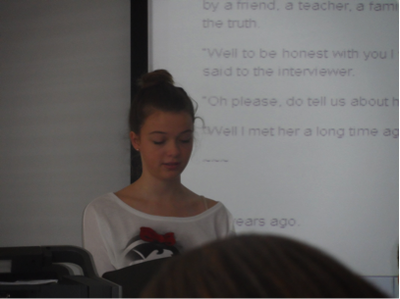

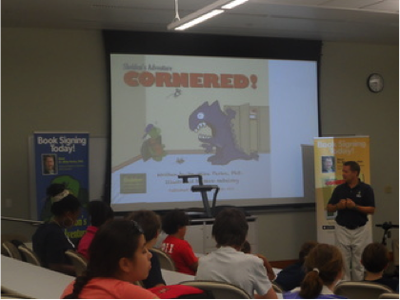

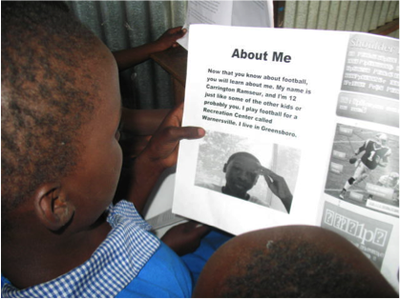

by Tresha Layne, Mark Meacham, and Amy Vetter Our previous blog described how we planned for the camp, including how those plans aligned with 21st century literacy goals (NCTE, 2013). This blog will discuss how those plans were put into action, including modifications we made based on the needs of participants. A typical day of the camp began with a whole group welcome in the UNCG School of Education auditorium and an author talk to inform and inspire young writers as they developed their camp publication piece. On the first day, campers met as a whole group in the auditorium to learn about some of their readers, students in Kenya. After her presentation, students asked questions, such as, “What do the kids eat the Melon Mission?” and “Is it hot there?” When students gathered in small group to brainstorm their writing, students also discussed how this audience shaped what they intended to write. For example, Jackson commented to two other campers that writing for children in Africa “changes the whole game” of writing for him. Such discussion about audience, then, began the process for students to think about how to design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes. All other camp days, began with an author. For example, on the second day of camp in 2014, a children’s book author described how he collaborated with a visual artist to create a multimodal children’s picture book. In sharing one of his tips on writing, he said, "find someone who completes you." After asking the young artists and then writers to identify themselves by raising their hands, the author said, emphatically, "get together . . . find someone who isn't exactly like you. That would be the best combination for creating a winning book." These interactions opened opportunities for students to foster connections and relationships with others that posed and solved problems collaboratively and strengthened independent thought. For example, after a poet shared his poetry, a high school student wrote poetry along with a non-fiction piece that he presented in a Prezi. In fact, some of the campers continue to stay in touch in with these authors and discuss their writing, so the collaboration and problem-solving persists even after camp is over. From there, writing teachers escorted students, divided by grade levels, to nearby classrooms equipped with computers and multimedia equipment. To develop proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools, teachers and writing coaches began with fifteen to twenty-minute whole group mini-lessons about 21st century literacy tools along with elements of the writing process before having students break into smaller writing groups for concentrated writing time and more individualized writing coaching and collaboration. For example, during a mini-lesson instructors demonstrated how a digital tool (Popplet) might be used to brainstorm and plan various kinds of texts. After learning about the tool many campers used it to help construct their texts. One camper, Sophie (rising eighth grader), used it to brainstorm and plan for a digital fashion magazine that utilized multiple modes of communication. In order to help campers develop proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools, teachers had to be intentional in their effort to comfortably use digital media tools themselves and had to be prepared to combat inevitable technical issues. From our observations, teachers’ comfort level in working with the digital tools played a big part in how well they were able to independently assist campers as they encountered issues with the digital tools. For the writing coaches in particular, many of the digital tools were new, so in some cases coaches were still learning digital tools along with their students. To resolve technical issues with digital tools in these cases, coaches relied on the support of camp colleagues or other campers. In some cases, resolving the technical issue required creative thinking. For example, one instructor had to figure out how to help a camper reformat his writing piece when it exceeded the allowable file size of the digital tool he wanted to use. To get around this limitation, the coach helped him remove his writing from the digital tool, place it into an alternate tool for special formatting, and then replace it in the original tool. To fully support campers’ ability to manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information and create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts, instructors and writing coaches anticipated the needs of the young writers. Most came with a planned mini-lesson based on the needs of the campers. For example, Maggie (a writing coach in the high school group) asked Jackson and Savannah to rewrite their opening sentence as a way to revise their final piece. To do this, both campers explored other first sentences of books, first lines of movies, and/or visuals (e.g., Jackson’s own drawings) as ways of hooking an audience. Both campers found this exercise challenging, but rewarding. In particular, when Jackson and Savannah shared their first sentences, they had the opportunity to critique and evaluate each other’s work in productive ways. Not all planned mini-lessons worked as writing coaches hoped they would. Although more stressful, they found that planning a lesson each night based on the needs of students worked better than entering the two weeks of camp with lessons already made. In addition, creating lessons that were interactive and situated students as experts fostered small group writing communities in ways that lecture-based instruction did not. Thus, teaching students about the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments (e.g., copyright), was more productive in small groups and when done while students were drafting and revising their pieces. Overall, making the camp a flexible, interactive, and informal writing community best supported students’ engagement in 21st century literacies. This included morning breaks with a brief snack and taking students outdoors for a quick writing break. In addition, concluding the camp with opportunities for young writers to share their writing at the university and a local bookstore enabled campers to share information with a broad audience. Audiences who attended these readings or read over the published pieces learned about the history of LEGOs, a thriller that involved shattered glass and a wounded father, and a drama about a kid who saved the world. Dividing these readings into manageable sessions (approximately 10 students for one hour) enabled students to share all or a portion of their work while not overloading the audience. Thus, campers needed time to practice reading aloud with a clear speaking voice and keeping within their allotted time limit. To read more about what we learned from the camp experience, check out our next blog. NCTE Executive Committee (2013). NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/governance/21stcenturyframework.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Contributors

Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed