Our Thinking

|

by Charise Kollar

“Miss, wanna take a selfie with me?” Having taught middle school and high school students, I am not a stranger to hearing this request on a regular basis. With the ever-evolving social media realm, students are constantly “plugged-in”, interacting with one another through visuals, audio, movies, pictures, and clips. The craving to share with one another is stronger than ever before, and educators are constantly being invited to the party. This year’s act of transitioning from the role of full-time teacher to full-time graduate student has brought about unexpected obstacles. Predominantly, one challenge that I did not anticipate being prevalent was my lack of “withitness” with evolving social media practices of students. Unknowingly, the adjustment to graduate school has resulted in the distancing from discovering “cool” new apps and innovative ways in which students use social media to communicate with one another. Luckily, I was given the chance to redeem some of my lost time in the classroom by participating in a leadership seminar for high school sophomores. This seminar, titled HOBY (Hugh O’Brian Youth Leadership), gives students the opportunity to build on their leadership abilities with the intention of instilling global change in any desired field. The students, who are referred to as ‘ambassadors’, are randomly placed into groups of ten. Within these small groups, the ambassadors participate in self-led, in-depth discussions about the content of the presentations and interactive activities with the help of a volunteer or ‘facilitator’. Unlike the common, traditional classroom, social media use is sporadically encouraged throughout the duration of the three-day seminar. The entire HOBY community participated in moments of expressive creativity, titled, “Social Media Blitz”. During these times, all cell phones reemerged from backpacks, purses, and pockets. Ambassadors loved having the opportunity to contribute to their individual social media communities. Admittedly, the staff and facilitators also took advantage of Social Media Blitz. Hashtags, such as #SoFLHOBY and #DaretoDeviate, were used to link all HOBY participants. The “wanna take a selfie?” question was running rampant. HOBY pride was everywhere, and everyone wanted to give themselves the HOBY stamp of participation via their social media accounts. On the last day of the seminar, the use for social media underwent a transformation. The ambassadors were exposed to a social charity called “Feeding Children Everywhere”, which allowed them to work together as a team in order to box over 10,000 meals in less than one hour. The human conveyor belt was assembled, and each ambassador assumed a specific role. While one member of the group poured in an exact ratio of dried beans, rice, and salt into a transportable bag, another member weighed the bag and iron-sealed it shut. And while every role was valued and vital to the packaging process, an additional role became just as prevalent: documenter. Documenting the event on Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook became an important step of the process. The ambassadors took ownership of their voices and chose to spread the word. Service is cool. Service can be a rejuvenating, social, and fulfilling process, and everyone should be given the chance to partake in making the world a better place. Through viewing this documentation process, I began to make connections between the impact of social media at HOBY and the potential impact that it can have in the classroom. How can educators effectively utilize social media to connect students with one another, while concurrently encouraging them to spread the word and promote their ideas, values, and passions? The ambassadors were true examples of proactive 21st century literacy advocates. The National Council of Teachers of English (2013) define the usage of 21st century literacies as being able to “build intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others so to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought”. Showing students that social media has the ability to not only connect and share ideas, it can also bring about solutions to global issues is a powerful responsibility that should not be bypassed by educators. The ability to interact with these bright and ambitious leaders was a reaffirming experience that critical thinking skills are alive and well, and that our students are continuously searching for ways to be relevant. Students are learning to adapt to the 21st Century literacy realm, and they are finding any avenue to have their voices heard. As educators, particularly English teachers, we focus on honing the voices of our students in their writing. Shouldn’t we promote this practice by way of social media, as well? Our students are not simply the leaders of tomorrow; they are making an impact today. It is our job to help them in this endeavor and encourage them to take a stance and responsibly utilize their voices in the most powerful and lasting way possible. Let’s accept our invitation to the party. References NCTE Executive Committee (2013). NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/governance/21stcenturyframework

9 Comments

by Katie Rybakova

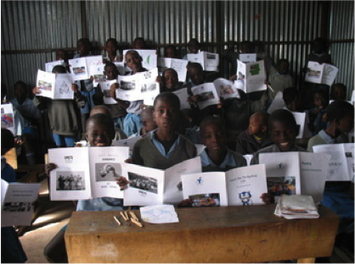

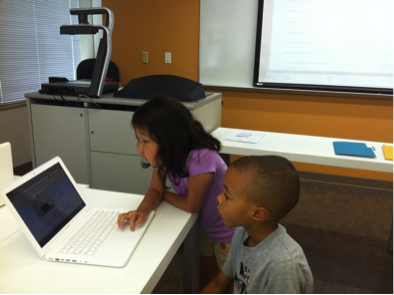

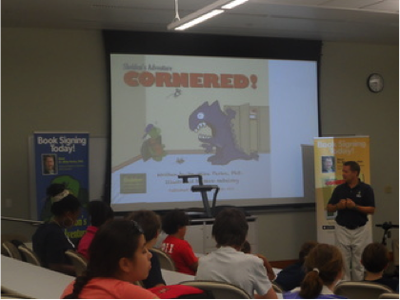

I was excited to teach multicultural literature online over the summer. I had been an online kid in high school (Florida Virtual) and always found online classes to be much more convenient because I was able to go at my own pace and study whenever it is that I wanted to. I approached teaching online the same way—the college students in English Education will be so ecstatic to take online courses, and those who did not have experience with online classes will grow to love them towards the end of the six-week course. Boy, was I wrong. From the syllabus to the way the discussion board was set up, my students had what felt like a question per 10 minutes. I set up a video to explain the syllabus to them by using a flip camera propped up my office desk directed at my face, but I doubted many people actually viewed it. Or, at least, it was hard to follow along with the syllabus on the screen at the same time. I’m not going to lie—I struggled to find inspiration that first week that would help my students understand what my expectations and processes were AND not lose my mind. I found what it was that I was looking for while trying to make a video to explain how to use JSTOR. I propped up my handy flipcam on my desk and aimed it at my computer screen, and explained how to use JSTOR to my students. Want to see my blurry masterpiece? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sqd4PFyQ90k&feature=youtu.be Now, of course, I was new to the whole screencasting thing, and at that point, I didn’t even know what it was. It was only towards the end of the semester that I realized I could capture what I had on my screen and record my voice (and even show everyone my excited face through webcam if I wanted to!) in a more eloquent and technologically savvy fashion. I started looking up screen casting software and “Screencasts” on YouTube. I found a variety of cool and useful tutorials. But, I didn’t find MY content tutorials. I decided to give it a try using screencast-o-matic.com. Awesome tool once you are able to download the screen recorder (which is not as intuitive as one would hope, especially for Mac users such as myself), and I had so much fun with it until I realized my capped free time was 15 min. I talk way more than that. So, a dilemma. How was I going to use this awesome new tool for my classes? Fast-forward about 5 months and my major adviser and I were the recipients of a technology grant from our university and we had at least 3 hours of recording time that renewed every month with a generous number of computer logins. Excitedly, I started thinking of tutorials, but it was hard to envision how I could use this tool now that it was fall and I was teaching a face-to-face class. In my fall class, I sat down with every student and talked to them about their lesson plans—it was their first time creating lesson plans and they liked the individual attention. Light blub—I could use screencasting for individual feedback. I told my students they were the guinea pigs for my new idea and that any feedback would be appreciated. I spent the next week recording screen casts of students’ lesson plans with my feedback in 5-6 min videos that I then emailed to each student individually. Now, it may seem like a lot of work, but I found that it actually cut time that I spent grading and giving feedback to student lesson plans. A typical 20 minute grading session per student became a 5 min reading and highlighting session and then another 5 minute screen casting session where I talked about the parts that I had just highlighted—good job here, I think you can write x, y, and z here, I think you made a great lesson but the content may be a little controversial so you’ll want to rationalize better. Then, about 2 minutes spent on waiting for the video to process into an mp3 file, and then sending the file as an email to the student (it was too large of a file to add into our typical blackboard feedback attachment). Now, 12 minutes versus 20 minutes, on average, may not seem like a big difference, but with 27 students that means instead of spending 540 minutes, or 9 hours, grading, I spent 324 minutes, or about 5.5 hours grading. I wasn’t as worried about the grading time as much as I wanted to make sure students were watching these videos and got the feedback they needed to help make them better. The response to these videos was incredible. All of my students really liked getting the videos that they can start, stop, pause, and restart anytime they wanted to. They felt like they were having a conference with me again, they got their individual attention, but they could “mini-conference” with me at any time instead of having a 15 min. block of time with me once during the semester. I used screencasting the next semester as well, with much the same response. I always changed up my feedback format—I would write on their lesson plans, old-school-style, one week, then do screen casting the next. I would then type my feedback into Word the following week, and conference face-to-face the next. When discussing ways in which feedback was given to students this semester, a lot of students mentioned the different forms of feedback they liked the best—some said screen casting, others preferred simple hand written notes. A teachable moment—everyone prefers something different, and so, we need to differentiate feedback as well as our instruction. In addition to feedback, I used screen casting for other purposes. I included tutorial videos of things that I felt were important for future assignments like an APA formatting guide video: http://youtu.be/HGA2f0BXBqI?hd=1 I had though about using other Youtube videos or screen casts to show tutorials, but I felt like by creating my own I a.) showed my effort to students and b.) made it more personal and individualized for our class. In terms of using the Screencast-o-Matic.com website itself, while there is a learning curve like with any tool, once you get the screen recorder downloaded as an application onto your desktop, it really is simple. You can drag and resize the frame to fit your entire screen, or a small little piece of the screen like above. Click on the red record button and you can begin! You can also, once you press record, pause your presentation and take a breath. If you want to include a webcam recording of yourself talking, click on the little webcam, the fifth button down from your left. Once you are done, you’ll get a chance to edit your presentation, cut out or crop parts you don’t want to include (you stumbling through words, or mispronouncing something, or someone knocks on your office door), and then save it. I save my videos to my computer then upload to Youtube as an unlisted video, or, if it’s feedback, I keep it on my computer then send it via email to protect the students’ identities. Want a screencast about screencasting? Here you go! https://youtu.be/gxcssZ2DnO8 Last year, I was videoing my screen using a flipcamera; this year, I have become a huge, huge fan of screen casting. I know it’s not the most “bells and whistles” form of technology, nor is it by any means new, but repurposing this technology has really helped not only my students but also me as I pursue the goal to become truly 21st century literate.  by Mark Meacham, Amy Vetter, and Tresha Layne Our past two blogs discussed our camp set-up and camp experience. In this blog, we explore what we learned from young writers at a summer camp dedicated to 21st century literacies. As campers engaged in small talk about fashion trends, Harry Potter characters, and which of several beginning sentences grabs the reader’s attention, we learned how young writers used this time to compose 21st century multimodal texts. In the following paragraphs, we discuss how campers sought feedback from instructors and each other, how they drew on individual conferences and, how they utilized tech tools shared during whole group mini-lessons to socially construct multimodal texts. In defining 21st century literacies, NCTE (2013) notes that individuals who practice 21st century literacies build intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others so to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought. From the start, as campers crafted stories, poems, and informational texts we found that they consistently called on instructors to read what they had written and to make suggestions for developing content. For example, in the first week, Katie (rising eighth grader), solicited feedback from Malik (instructor). During their interaction, Katie shared details of her life and explained why she chose to create characters that identify as gay. As a writer, then, she explored with an instructor how she draws on aspects of her identity to create characters that are, as she told Malik, “not so stereotypical.” From this example, and others like it, we learned informal social interaction centered on the craft of writing served to foster campers’ thinking about who they are as writers and what motivates them to write. Katie said she wanted to share stories that “are not so straight-oriented,” that reflect who she is. In the end, Malik responded in a way that both supported her identity construction as writer and motivated her to continue constructing a text that, in Malik’s words, “can fill in a space that is a void.” Thus, when campers like Katie utilized social interactions to solicit feedback from instructions, we observed not only how 21st century literacies might be collaborative in nature, but also how that collaboration might foster young writers’ identity and text construction, and strengthen youth’s independent thought. Another way young writers posed and solved problems collaboratively, was by calling on each other to help with ideas for plot. During day eight, for example, Haley (rising tenth grader) asked Katie to provide a word that describes how two characters might show affection for one another. Katie suggested she use “coddling” because it connotes a mother-child relationship that is “not, like, romancy.” As they continued discussing the scene, Katie asked clarifying questions and shared ideas for describing the characters’ actions. In other words, Katie helped Haley with a problem associated with plot. This kind of interaction suggests text construction was not only collaborative, but often involved problem-solving. In fact, certain interactions between campers at times, involved one camper composing lines of text for another camper’s story. We also learned that young writers utilized support from instructors and writing coaches to develop proficiency and fluency with tools of technology, manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information and create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts. To help young writers understand that text construction is multimodal, instructors designed and presented mini-lessons to share digital tools that aid in the writing process. While instructors interacted with campers, they encouraged campers to use the tools to brainstorm, plan, edit, and cite sources. For example, as he constructed a website, Zeke (rising eighth grader) created a digital comic using a tool (pixton) instructors shared during a mini-lesson. In explaining the comic’s design, Zeke noted he “chose a kid [as a character]” because he wanted to show how a kid may “want to volunteer when he gets older.” Zeke said he did this because kids may “want to help out so other people can study too.” Sharing comic strip makers such as pixton, thus, fostered Zeke’s construction of a multimodal digital text that served, as he noted, to engage his audience. We also discovered, for some campers, digital technology was not only used to share drafts and solicit feedback, but was also used to extend audiences and engage in social action. This aspect of 21st century literacies suggests problem-posing and solving often involves designing and sharing information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes (NCTE, 2013). In constructing his website, Zeke researched the Kenyan students’ daily activities, located pictures online, created a survey about volunteering, and learned how his audience might use his website to support the Melon Mission Project. For one page, he created a forum through which his audience could interact with him and other visitors to the site. During a short conversation, Ray (researcher) asked Zeke about the purpose of the forum. He said, “people can have a conversation and I can go and answer any of the questions they might have.” For another camper, Rosalyn (rising eleventh grader), framing text construction as multimodal provided opportunities to educate her audience about subtle messages associated with media consumption. For her text, Rosalyn created a multimodal blog using another of the digital tools (weebly.com) we shared during a mini-lesson. Both Rosalyn and Zeke, then, composed texts that were linguistic, visual, and aural, in other words, multimodal. In the end, sharing digital tools opened opportunities for campers to reach audiences outside the confines of the camp and, in Zeke’s and Rosalyn’s case, to engage those audiences in social causes. As we reflected on the camp, we learned that providing extended periods of time and sharing digital tools fostered text construction. As campers worked to create blogs, websites, or animated comics, their composition process was social, collaborative, and multimodal. Given these findings, we plan to open more opportunities for campers to be socially interactive and student-centered to foster campers’ 21st century literacies. One of those goals includes providing opportunities for students to work in our School of Education’s Self Design Studio to promote creativity. NCTE Executive Committee (2013). NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/governance/21stcenturyframework  by Tresha Layne, Mark Meacham, and Amy Vetter Our previous blog described how we planned for the camp, including how those plans aligned with 21st century literacy goals (NCTE, 2013). This blog will discuss how those plans were put into action, including modifications we made based on the needs of participants. A typical day of the camp began with a whole group welcome in the UNCG School of Education auditorium and an author talk to inform and inspire young writers as they developed their camp publication piece. On the first day, campers met as a whole group in the auditorium to learn about some of their readers, students in Kenya. After her presentation, students asked questions, such as, “What do the kids eat the Melon Mission?” and “Is it hot there?” When students gathered in small group to brainstorm their writing, students also discussed how this audience shaped what they intended to write. For example, Jackson commented to two other campers that writing for children in Africa “changes the whole game” of writing for him. Such discussion about audience, then, began the process for students to think about how to design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes. All other camp days, began with an author. For example, on the second day of camp in 2014, a children’s book author described how he collaborated with a visual artist to create a multimodal children’s picture book. In sharing one of his tips on writing, he said, "find someone who completes you." After asking the young artists and then writers to identify themselves by raising their hands, the author said, emphatically, "get together . . . find someone who isn't exactly like you. That would be the best combination for creating a winning book." These interactions opened opportunities for students to foster connections and relationships with others that posed and solved problems collaboratively and strengthened independent thought. For example, after a poet shared his poetry, a high school student wrote poetry along with a non-fiction piece that he presented in a Prezi. In fact, some of the campers continue to stay in touch in with these authors and discuss their writing, so the collaboration and problem-solving persists even after camp is over. From there, writing teachers escorted students, divided by grade levels, to nearby classrooms equipped with computers and multimedia equipment. To develop proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools, teachers and writing coaches began with fifteen to twenty-minute whole group mini-lessons about 21st century literacy tools along with elements of the writing process before having students break into smaller writing groups for concentrated writing time and more individualized writing coaching and collaboration. For example, during a mini-lesson instructors demonstrated how a digital tool (Popplet) might be used to brainstorm and plan various kinds of texts. After learning about the tool many campers used it to help construct their texts. One camper, Sophie (rising eighth grader), used it to brainstorm and plan for a digital fashion magazine that utilized multiple modes of communication. In order to help campers develop proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools, teachers had to be intentional in their effort to comfortably use digital media tools themselves and had to be prepared to combat inevitable technical issues. From our observations, teachers’ comfort level in working with the digital tools played a big part in how well they were able to independently assist campers as they encountered issues with the digital tools. For the writing coaches in particular, many of the digital tools were new, so in some cases coaches were still learning digital tools along with their students. To resolve technical issues with digital tools in these cases, coaches relied on the support of camp colleagues or other campers. In some cases, resolving the technical issue required creative thinking. For example, one instructor had to figure out how to help a camper reformat his writing piece when it exceeded the allowable file size of the digital tool he wanted to use. To get around this limitation, the coach helped him remove his writing from the digital tool, place it into an alternate tool for special formatting, and then replace it in the original tool. To fully support campers’ ability to manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information and create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts, instructors and writing coaches anticipated the needs of the young writers. Most came with a planned mini-lesson based on the needs of the campers. For example, Maggie (a writing coach in the high school group) asked Jackson and Savannah to rewrite their opening sentence as a way to revise their final piece. To do this, both campers explored other first sentences of books, first lines of movies, and/or visuals (e.g., Jackson’s own drawings) as ways of hooking an audience. Both campers found this exercise challenging, but rewarding. In particular, when Jackson and Savannah shared their first sentences, they had the opportunity to critique and evaluate each other’s work in productive ways. Not all planned mini-lessons worked as writing coaches hoped they would. Although more stressful, they found that planning a lesson each night based on the needs of students worked better than entering the two weeks of camp with lessons already made. In addition, creating lessons that were interactive and situated students as experts fostered small group writing communities in ways that lecture-based instruction did not. Thus, teaching students about the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments (e.g., copyright), was more productive in small groups and when done while students were drafting and revising their pieces. Overall, making the camp a flexible, interactive, and informal writing community best supported students’ engagement in 21st century literacies. This included morning breaks with a brief snack and taking students outdoors for a quick writing break. In addition, concluding the camp with opportunities for young writers to share their writing at the university and a local bookstore enabled campers to share information with a broad audience. Audiences who attended these readings or read over the published pieces learned about the history of LEGOs, a thriller that involved shattered glass and a wounded father, and a drama about a kid who saved the world. Dividing these readings into manageable sessions (approximately 10 students for one hour) enabled students to share all or a portion of their work while not overloading the audience. Thus, campers needed time to practice reading aloud with a clear speaking voice and keeping within their allotted time limit. To read more about what we learned from the camp experience, check out our next blog. NCTE Executive Committee (2013). NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/governance/21stcenturyframework. by Amy Vetter, Mark Meacham, and Tresha Layne For the past three years, the University of North Carolina Greensboro has hosted a two-week Young Writers’ Camp for students in grades 3-12. After the first year, the committee decided to dedicate the two-week camp to 21st Century Literacies. In other words, we wanted to create a space for young writers to collaborate with other writers, read and produce multimedia texts, and share information with other young writers across the globe. The purpose of this blog is to write about how teacher educators, doctoral students, and public school educators’ worked together to set up a camp dedicated to writing in the 21st century. Two blogs will follow that describe how the camp actually worked and what we learned from the process. The first year of our camp was split into two sections: one dedicated to creative writing and one dedicated to informational texts. As former and current K-12 teachers, we viewed the focus on these two areas of writing to be limiting for students. In addition, the divide between the two did not illustrate the realities of writers today. Starting the second year, campers attended both weeks, chose to write in their preferred genre, and used digital media to construct and publish their final piece. To prepare for this new vision, we developed a shared understanding of what we meant by 21st century literacies. Specifically, we drew from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) (2013) who state that participants of 21st century literacies, do the following: ● Develop proficiency and fluency with tools of technology ● Build intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others so to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought ● Design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes ● Manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information ● Create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts ● Attend to the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments To create a camp that fostered the above characteristics, we first collaborated with colleagues at our university and surrounding public schools. To begin, we hired four instructors (certified literacy teachers) and placed them in rooms with 15 campers divided by grade level (3-5; 6-8; and 9-12) who met for two weeks from 9 am to 12 pm. We had two elementary groups. Along with the instructors, we worked with faculty members who taught a graduate-level Teaching of Writing Course that occurred during the two weeks of the camp. Instructors agreed to use the camp as a field placement for graduate students (all K-12 certified literacy teachers) to try out strategies they learned in their course. The faculty members who taught this course prepared the “writing coaches” to engage in a writing workshop approach, including planning mini-lessons based on the specific needs of campers. Students also read various texts to help prepare them for this endeavor, such as Crafting Digital Writing: Composing Texts Across Media and Genre by Troy Hicks. In addition, writing coaches and instructors came prepared to help campers manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information and create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts by sharing mentor texts and guiding students through research strategies for both creative and informational texts. Along with these instructional approaches, writing coaches and instructors planned to educate campers about ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments, including copyright issues and plagiarizing. To help with this, we hired two technology coordinators who created email usernames and passwords that we gave to parents to ensure online safety, especially with the younger campers. We also bought flash drives for campers to save their material so that if they did not have to access to the web after camp, they could work on their piece at home. Finally, our instructional approach included the development of proficiency and fluency with specific digital media tools that campers used, such as Voicethread, Weebly, and Comic Life. To help prepare those teachers for these new tools, the camp committee developed a list of resources campers could use, along with some information about how to use them with young writers (definition, examples, links to tutorials, and suggestions for exploration). Writing coaches and instructors in the elementary group decided to focus on a select amount of mediums, while middle and high school were open to choosing whatever digital media tool students preferred. To foster intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others that posed and solved problems collaboratively and strengthened independent thought, we contacted local and national authors about speaking with our young writers about their work and their writing process. We invited novelists, poets, children’s book authors, bloggers, journalists, graphic artists, documentary producers, etc. Some authors lived in the area, while others Skyped in from other cities and states, such as New York. These authors were asked to share their writing, discuss their writing process, and answer questions from the audience. All of the authors were expected to interact with students and engage them in some kind of composing activity. Feel free to browse our author list. We also worked with developers of The Melon Project, a non-profit organization that works to better the lives of children and their families living in Nakuru, Kenya. One of the objectives of the organization is to offer basic education to the orphans and destitute so as to join the mainstream of other school going children. For the first day of each camp, we asked an organizer of The Melon Project to describe the purpose and people behind the organization. We planned to have published pieces from our young writers to be sent to Kenya and used as a learning tool for these children, especially to aid in the learning of English and American culture. This enabled campers to design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes. Campers also read aloud their published pieces on the last day of camp with an audience of community members (i.e. family members and local educators) and/or at Scuppernong, our local bookstore. Check out our camp publications here. Although we planned for the camp to work as described, we made modifications based on the needs of our campers, instructors, writing coaches, and access to digital media. In our second blog, we discuss how the camp actually worked, including more details about the ways in which campers engaged in the specified characteristics of 21st century literacies. NCTE Executive Committee (2013). NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. Retrieved from: http://www.ncte.org/governance/21stcenturyframework. Hicks, T. (2013). Crafting Digital Writing: Composing Texts Across Media and Genre. New York, NY: Heinemann. by Kathy Garland

I teach a course called, Teaching Literature and Drama in High Schools. It is one of a set of initial courses that our undergraduate students are required to take. During this class, students read Critical Encounters (Appleman, 2009) and Doing Literary Criticism (Gillespie, 2010), anchor texts that demonstrate how to use critical theories, such as gender or Marxist theory in secondary language-arts classes. Additionally, students read a variety of canonical novels (e.g., Black Boy, The Great Gatsby) and young adult novels (e.g., Diary of a Part-time Indian, Yummy) in order to apply the theoretical principles to novels they may have to teach in authentic contexts. And because my research and background are heavily rooted in media literacy education and popular media, I nudge future teachers to consider using everyday texts, such as YouTube videos, documentaries and other media as relevant connections for their future students. As of late, I’d been concerned that students were learning theories and pedagogy that were antithetical to the scripted and high-stakes testing culture that is omnipresent in many public schools. That was until I received an assignment from Tatiana. Tatiana completed Teaching Literature in 2013. She is currently finishing her practicum with me. Part of her assignments requires that she teach mini-lessons and quantitatively “prove” that students have learned specifically due to her instruction. For her mini-lessons, Tatiana’s cooperating teacher asked her to reinforce students’ understandings of point of view. Instead of choosing an irrelevant issue, Tatiana decided that one of her mini-lessons should focus on the Mike Brown shooting. When asked why she chose this particular topic, Tatiana said, “I thought it was important to bring what is happening in Ferguson into the classroom in order to create active and educated students.” She began with the idea that English teaching should not only be content-based, but that it should also be significant to students’ lives. Tatiana had autonomy in text selection. Therefore, her next steps included choosing two appropriate and credible online texts. One was from the New York Times, the other from The Washington Post. Both articles presented information about Mike Brown, but they differed in tone and diction. For example one article depicted Mike Brown as a “thug,” while the other portrayed him as an innocent victim of police brutality, thus illustrating one of her objectives: Students will be able to experiment with the effectiveness of different points of view in writing, comparing and contrasting different points of view. I was fortunate enough to observe Tatiana’s lesson using these two online sources. Students were not aware that their articles were about the same person: Mike Brown. Students were separated into groups. Each group read one article and then noted how Brown was portrayed. Students also had to provide textual support for their answers. Small groups seemed productive and engaged as they noted specific words that demonstrated a particular tone. Tatiana then drew two T-charts on the board and asked groups to share the diction from their articles. Positive words were written on the first chart, and negative words were written on the second one. After both lists were exhausted, Tatiana revealed that the articles were actually about the same person. She also explained how media use certain language in order to create a specific point of view that may in turn change how a person or a situation is perceived. This lesson was brief; however, it allowed Tatiana to complete a few academic goals: (1) she was able to scaffold information about tone, diction and point of view, common staples in language arts curricula; (2) she was able to integrate media analysis and present students with a method for understanding how language is used to construct media and shape public opinion; and (3) she was able to conduct a focused discussion centered on a relevant social issue. Tatiana believes that “it is important to arm our students with the ability to understand when media is creating a certain point of view through the use of language and tone,” and I agree. I would also add that language-arts teachers have a responsibility to teach literacy skills and relevant social justice issues through a myriad of texts. Using online media sources is one way to do this. I’d love to hear about the ways that you have used media texts in order to teach literacy skills and prevalent societal issues. Perhaps we can inspire one another to add a little relevancy to our existing curricula. References Alexie, S. (2007). The absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian. New York, NY: Hachette Book Group USA. Appleman, D. (2009). Critical encounters in high school English: Teaching literary theory to adolescents. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Eligon, J. “Michael Brown spent last weeks grappling with problems and promise.” The New York Times. 24 Aug. 2014. Web. 18 Sept. 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/25/us/michael-brown-spent-last-weeks-grappling-with-lifes-mysteries.html?_r=0 Fitzgerald, F.S. (1925). The great Gatsby. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s sons. Gillespie, T. (2010). Doing literary criticism: Helping students engage with challenging texts. Portland, ME: Stenhouse. Lowery, W., & Frankel, T. “Mike Brown notched a hard-fought victory just days before he was shot: A diploma.” The Washington Post. 12 Aug. 2014. Web 18 Sept. 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/mike-brown-notched-a-hard-fought-victory-just-days-before-he-was-shot-a-diploma/2014/08/12/574d65e6-2257-11e4-8593-da634b334390_story.html Neri, G. (2010). Yummy: The last days of a Southside shorty. New York: Lee and Low Books, Inc. Wright, R. (1944). Black boy. Cutchogue, N.Y: Buccaneer Books, Inc. We are excited to share our international collaboration publications, published with the Literacies and Second Languages Project. The LSLP is led by Raúl A. Mora, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellín (Colombia).

Pinterest and 21st century literacies by Katie Rybakova and Charise Kollar: http://www.literaciesinl2project.org/uploads/3/8/9/7/38976989/lslp-micro-paper-9-pinterest-and-21st-century-literacies.pdf Participatory Literacies by Rikki Rocanti: http://www.literaciesinl2project.org/uploads/3/8/9/7/38976989/lslp-micro-paper-10-participatory-literacies.pdf Livescribe and Second Language Learning by Amy Piotrowski: http://www.literaciesinl2project.org/uploads/3/8/9/7/38976989/lslp-micro-paper-13-livescribe-and-second-language-learning.pdf You can view other Micro-Papers at http://www.literaciesinl2project.org/lslp-micro-papers.html by Rikki Roccanti There is no easy way around teaching classic literature. We try to make it interesting – or at least as painless as possible. We try to fit the movie adaptation into our busy curriculum. We try to incorporate technology. We try to find YouTube videos that relate. In effect, we are trying to pull these classic texts into the 21st century. Good news. There are other people working on this as well, and they have done much of the hard work for us. The name of our hard-working savior is Pemberley Digital (http://www.pemberleydigital.com), a web video production company that creates modernized adaptations of classic texts through the use of new media platforms. The company began this venture with their adaptation of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, The Lizzie Bennett Diaries, which won an Emmy in the field of outstanding creative achievement in interactive media. The video series, produced by Hank Green and Bernie Su, envisions Lizzie Bennett as a vivacious, 24 year-old master's student creating a video dairy for a final project in a mass communications class. In addition to The Lizzie Bennett Diaries, Pemberley Digital is currently producing Emma Approved, an adaptation of Austen's novel Emma. For their next project, which will begin in August, the company is teaming up with PBS and breaking-ground on non-Austen classic with the creation of Frankenstein, MD which will reimagine the protagonist of Mary Shelley’s novel as Victoria Frankenstein, a female physician obsessed with proving herself in the male dominated field of medicine. As modernized adaptations, these video series reimagine many of the details of the classic novels but include the main characters and follow the same general plot. The details of the novel change because they are refashioned into a form that contemporary audiences would more readily understand and to which they could relate. For instance, Darcy's house, Pemberley, does not exist in The Lizzie Bennett Diaries. In the video series the significance of Pemberley is transferred to the company Darcy runs, Pemberley Digital (which the series' production company eventually adopted as its name). Houses were signifiers of wealth, status, and identity in Regency England, so the series producers translate what Austen was trying to signify through Darcy's house to a modern day signifier – a company run by Darcy – in order to retain a sense of meaning for a contemporary audience. Not only does Pemberley Digital modernize the adaptations through contemporary signifiers, but they also pull Austen's classic novels into the twenty-first century through the use of transmedia storytelling practices which communicate elements of the story through new media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, Linkedin, and Lookbook,. These venues serve to further immerse audiences in the story worlds of the adaptations as well as serve as interfaces which encourage audience participation through feedback as well as the collection, sharing, and discussion of story content. In the series Emma Approved, Emma Woodhouse is a matchmaker and lifestyle expert at Highbury Partners Lifestyle Group, and as such she uses her Twitter, Pinterest, Facebook, and Tumblr pages to keep everyone tuned into her work life. For example, when Emma throws a bachelor’s auction as part of a benefit on human rights (the equivalent of the ball scene in Emma) Emma does not bring her video camera with her to the auction but @EmmaApproved tweeted about what was happening at the event to keep audiences engaged until the next video came out to recap the auction. While these modernized, transmediated adaptations are of course entertaining on their own, they could also be easily incorporated into a middle or secondary English class teaching one of the classic novels. Each video is only around 4-7 minutes long which would make for a nice opening activity to transition students to talking about the novel. But the stories created by Pemberley Digital are not merely tools to distract students from the original novels or to keep their eyes from falling shut. These stories provide students with new ways to interact with old stories through the use of new media and participatory practices. These stories are providing students with new ways to “read” and engage with class literature. The stories can also open up interesting discussions about why the producers made the decisions they did in adapting the show. What have they changed and why? Does the story retain the same meanings? How are the producers using social media to add to the story? Not only can these stories serve as a means to analyze the classic novels, but their transmedia characteristics create gaps which encourage further expansion. For instance, students could create their own v-logs telling the story from another character’s point of view or from a scene (like the dance in Emma) that was discussed but not shown. However you use these stories in your classroom, Pemberley Digital can attest to the fact that classic literature still intrigues and delights us. And it continues to inspire us. It inspires us to create our own stories out of the woodwork of timeless texts. And it inspires us to find new ways to keep the story timeless by utilizing the tools of 21st century storytelling to reach a new generation of young adults. By Kathy Garland

When I taught high-school English, I remember creating a project that required students to locate, interpret and analyze popular music. The example that I gave them included music centered on line dances. You know songs like, Electric Boogie (Slide) (1989) or Boot Scootin Boogie (1992)? Together, we listened in class and read the lyrics. And then, we interpreted and analyzed these songs and words in terms of literary devices and patterns. I challenged them to find their own appropriate popular songs so that they could do the same. Sounds like fun, right? It was. However, that was before Ty Dolla Sign, Nicki Minaj or Two Chainz! Music has changed, but students are still listening. So what’s a language arts teacher to do in the 21st Century? Here are some suggestions based on your level of popular song knowledge: 1. You are familiar with popular songs. Use the clean version. If you’ve recently listened to any popular songs, then you might have noticed that there are two major subjects: sex and drugs. Therefore, using the clean version might be helpful. However, I would only suggest this if you are familiar with either the artist, or the lyrics. For example, one language arts teacher I spoke with once began class by rapping the words from Gorilla Zoe’s Hood Figga (2007), a very explicit song. He used the song to better explain the characteristics of American Romanticism. He was well established in his career, familiar with hip-hop and rap culture, and knew his students, school and district, so this lesson worked out well for him. 2. You know some popular songs from the last ten years. Integrate one song that supports the curriculum. Find that one song you really like that will not make you look as if you haven’t watched videos in decades. Locate similarities between that song and another mandated curricular text. I recently interviewed a senior, high-school teacher who guided students through a comparison of Beyoncé’s, If I Were a Boy (2008) to Judy Brady’s Why I Want a Wife (1972). According to her, students were surprised by the similarity in theme even though the mediums are different and the writers are decades apart. Imagine the other possibilities for this culturally relevant method for teaching. 3. You know zero popular songs. Consider flexible assignments. Are your students writing? If so, then ask them to list ten popular songs that they might be listening to. Perhaps follow-up questions might encourage them to give supporting details for their songs’ similarities, or maybe ask students to provide rationales for listening to this type of music. In addition to learning about what your students find important, they will also practice using literacy practices deemed important for academics. This brief question might later turn into a writing assignment where they defend today’s popular music. YouTube, Pandora, Spotify, I Heart Radio, the list is endless for how our students are currently listening to music. These 21st century tools have made popular music more accessible. And as language arts educators, we should be mindful of how students are processing the texts of their lives. Any of these suggestions can be extended to teach about specific artists and their word choices; likewise, these activities can be used as methods for supporting students as they examine their own sociocultural worlds that are oftentimes rooted in popular music. How do you currently use music in your secondary language arts class? Feel free to comment with your recommendations as these might be useful for someone looking for a fresh start to a new year. References Brady, J. (1971). Why I want a wife. The Bedford Reader. XJ Kennedy, Dorothy M. Kennedy. Beyoncé. (2008). If I were a boy. On I am…Sasha Fierce. [CD]. Columbia. Brooks & Dunn. (1992). Boot scootin boogie. On Brand New Man. [CD]. Arista. Gorilla Zoe. (2007). Hood figga. On Welcome to the Zoo. [CD]. Bad Boy/South Block Entertainment. Griffiths, M. (1989). Electric boogie. On Carousel. [CD]. Reflections on "Reflections on a Gift of a Watermelon Pickle" and Our Roles as Literacy Cheerleaders6/3/2014 by Shelbie Witte

One of the first books of poetry I ever read as a child happened to be the first book of poetry I ever taught as a teacher in the classroom. "Reflections on a Gift of Watermelon Pickle", published in the late 1960's, was a ground-breaking compilation of poetry that specifically appealed to the 'modern' adolescent. Poems by Eve Merriam, Sy Kahn, Carl Sandburg, Ezra Pound, and dozens of others were representative of the great works of literature that spoke to our hearts as readers. As teachers, it became a critical reference text for short pieces of literature that would motivate and engage our students to want to read more, write like, and experience literacy through creative voices. My favorite from "Reflections" is by Eve Merriam: "How to Eat a Poem" Don't be polite Bite in. Pick it up with your fingers and lick The juice that may run down your chin. It is ready and ripe now, whenever you are. As teachers, we often serve in the role of literacy cheerleaders, offering our students multiple avenues and doors into the world of texts. As our world evolves, so do the texts that motivate and engage. Indeed, the very meaning of "text" has also changed, making our list of critical reference texts even more diverse. What texts move your students to devour their words? How do you encourage your students to eat a poem, a novel, a text? |

Contributors

Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed